A Little Côte de Beaune

Picking up a few bottles for a picnic in Pommard

I’ve always avoided Burgundy wines, those famous Pinot Noirs and Chardonnays. Mostly because they are prohibitively expensive, but if I am being brutally honest, I never like the way Burgundy “wine people” act. They seem to be somehow purposefully apart from the rest of the wine world. They look at me with something between cluelessness and disdain when I bring up other wines in conversation. Superb northern Rhônes, or Washington wines made from Syrah…blank stare. Oregon wines, also made from Pinot and Chard…chuckles. Barolo, made from Nebbiolo, somewhat Pinot-like…discomfort. Left bank Bordeaux, blends of Cabernet and Merlot…snarled upper lip.

I remember about a decade ago when I was living in Los Angeles and I became friends with the very talented and highly successful artist, Chis Trueman. You might think that art would have been our common denominator, but no, it was wine. We actually met at a tasting event at The Wine House in West LA. Chris is the nicest guy in the world, and it was my luck to cross paths with him, but he was also a Burgundy guy. He wasn’t like the above description at all because, thankfully, he liked to drink all kinds of good wines, but he liked Burgundy the most and when he spoke about them, I always felt left behind. He knew the minutiae of vineyards and makers that seemingly required a degree in cartography or geography to understand. It was as if he was speaking French to me before I could understand the language. That’s really an apt analogy. I understand a lot of French now and I am also deeply into Burgundy. I am not yet fluent in either, but I am enjoying the heck out of the journey getting there.

The best pastry in Beaune is here

In Beaune, there are wine bars and restaurants on every corner

Beaune is green and beautiful

Wandering through the streets of Beaune

Even the Berkeley wine seller, Kermit Lynch, has an office in Beaune

I spent ten days there last year and I just returned from another six-day stint last week after Chien-hui and I reconnected with Mark and Marie after their month in Noyers-sur-Serein for her artist residency. We all stayed together at a lovely two-bedroom apartment in Beaune called Beaune Sweet Home. It is at this point that I will switch to using the actual name of the region, Bourgogne (Bor-Go-Nyuh) out of respect for the French. We don’t anglicize any other region of France (Champagne is Champagne, and Provence is Provence) so why have we decided to call Bourgogne, Burgundy? The city of Dijon, where we stayed last year, is the largest in the region of La Région Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, but the true heart of the wine region is Beaune (Bōne). If there was ever a place designed for me, it’s Beaune. Nothing but boulangeries, dozens of wine shops, numerous wine bars, and hundreds of restaurants, along with a few museums and parks sprinkled in, all contained within a medieval city that maintains its history and architecture beautifully. The best part is that the entire city is surrounded by the world’s most famous vineyards for miles to the north and south—from the center of Beaune to the first site of the vines is less than eight minutes by car in any direction.

Vineyards are so close to Beaune

Everyone who lives in Beaune, and whoever visits, is there for one reason and one reason only: Wine. And that is certainly what we were there for. I built an itinerary for the four of us that included visiting two domains every day, with a scheduled lunch in between, and a fabulous dinner each evening. I will remind anyone reading this and considering a similar adventure to make your reservations well ahead of time. Yes, there are roadside wineries that you can just happen upon for tastings, you will see the signs when driving around, but they aren’t usually the best quality producers. The restaurants fill up every night, so reservations are an absolute must.

1247 named regions in Bourgogne, these are just the most famous

Holding a pice of ancient seabed limestone in the walled vineyard of Le Village, in Volnay

Brown limestone soils and limey-clays in Puligny-Montrachet

The best part of traveling with Mark and Marie is that they have the same appetite for food and wine as me, and they get as excited about where we are going to eat as I do. Plus, they don’t seem to mind at all when I want to pull over and run into some famous vineyard and grab handfuls of soil and then ask them to take my photo. Every night we ate at restaurants that were better than the night before, which didn’t seem possible because they were all so damn good. One night we ate at the farmhouse, L’Auberge Des Vignes, in Volnay, sitting next to the vines as the sun went down. Another night we ate superb Vietnamese food paired with the best Monthelie, a white Bourgogne made of Chardonnay, at The Slanted Door. The sommelier there was so friendly that she even directed us to the best wine bar I had ever been to after we finished dinner (Le Bout du Monde). I have never seen so many young people in large groups enjoying so many bottles of good wine. The wine list there was about an inch thick and as I looked around the room, I saw what looked like five or six people studying for an exam, but no, it was just the wine list. I mean people were studying it. I know younger people are not drinking as much these days and the wine industry has taken a 20% hit as a result, but not at this place, that’s for sure. The next evening we had very fancy boeuf Bourgogne at Le Cheval Noir, a classic French restaurant where the other guests come in with small dogs. It was very French and we felt very young. The final night we really outdid ourselves, and ate at the Michelin-starred restaurant, Clos de Cèdre. That meal peeled our heads back and took our tongues on an elevated journey. But there was also one night where we just ate cheese and crackers on the porch and listened to the rain while we drank a great bottle of wine.

L’Auberge Des Vignes, in Volnay

Mark studying the wine list at Le Bout du Monde

Rhubarb dessert with Champagne foam and jelly at Clos de Cèdre

As for the Domains we visited, we started with a visit to Maison Chanzy in Puligny-Montrachet where we sat outside at a table under a wide white umbrella protected from the glorious sunshine while we enjoyed charcuterie boards of superb cheeses and meats and we tasted reds and whites from the Côte de Beaune and the Côte Chalonnaise, two regions in central Bourgogne. Mason Chanzy is one of the ten largest producers in Bourgogne, and they showed their wealth with their beautiful tasting room and a spectacular garden that felt like some kind of estate that we were privileged to enjoy. Fortunately, their size didn’t seem to diminish the quality of their wines.

Our next stop was another part of Bourgogne that felt truer to its origins; a small producer off of a tiny back alley in Pommard. When I knocked on the door of the small family farmhouse, I could hear the family inside enjoying their lunch. We were a few minutes early to our 2:00pm appointment, and I should have known better as I have already learned that the French are 15 minutes late to everything, and lunch is practically a government protected event, so when they finally came to the door, they seemed surprised to see us. After we exchanged Bonjours, the older gentleman explained that his son, Guillaume Baduel, whose domain we were there to see, was away and instead, he would be taking us on the tour. Like most of the vignerons in Bourgogne, five or six successive generations of the family have owned the Domaine, worked the vines and made the wines, and here was no different as Guillaume had recently taken over the business from this man, his father. So, he was certainly qualified, perhaps more so, to take us past the tractors under the shed awnings, into the barn, past the presses and the tanks, and down the tiny spiral stairs to the cellar where the sleeping barrels lay, explaining everything we saw in his thick French accent as we followed behind.

Unlike Maison Chanzy which required large warehouses in multiple locations in Bourgogne to store their wines, everything that Domaine Guillaume Baduel made was here under the floor of their farmhouse. Barrels with the names of wines from vineyard plots written in chalk on their faces, I recognized one vineyard that we had drunk the night before from a different producer. The land is so valuable in Bourgogne and has been so divided up over the centuries by inheritance laws, that makers often only own a few rows from the same vineyards. The four of us, our eyes wide, felt like we had been given the keys to some backstage where we could see the “real” Bourgogne. When we finally got to tasting wines, we were in the deepest, coldest part of the cellar, and an entire row of lights had burned out, which the man apologized for as he smiled and waved at the darkness. The shadows were deep from the one remaining row of lights left burning, heightening the drama of what we were putting in our mouths. These were not mass-produced wines, rather we tasted the heart and soul of this family. Each wine was very different, even from the same vineyards where we had tasted the other maker’s wine, as we tasted red fruits, earth, spices, and minerality. Guillaume’s fingerprints transferred from vineyard, to barrel, to our glasses, the very definition of terroir, that elusive French word.

The tasting room at Maison Chanzy in Puligny-Montrachet

Tasting small producer wines at Domaine Guillaume Baduel

A barrel of Monthelie Les Sous Roches at Domaine Guillaume Baduel

Tasting some really fine wines with Arthur at Armand Heitz in Pommard

Our guide, Arthur, takes us through the walled vineyards, or Clos, of Pommard

Visiting the single premier cru monopole Clos des Poutres in Pommard

Looking west towards the premier cru vineyards on the hill between Volnay and Pommard in the Côte de Beaune

We scheduled free time for everyone the next day, or rather we didn’t schedule anything at all, but we still managed to walk to see the Hotel Dieu, the old hospital for the dying poor, the Hospices de Beaune, that ran uninterrupted from the late 1400s until the early 1980s. It’s certainly the most famous place in Bourgogne, and the colorful tiled roof is recognized globally as a symbol of Bourgogne. It has a truly fascinating history and is an absolute must-visit if you find yourself in the area. One of the wonderful things about the Hospices de Beaune is that it was funded by a wine auction each year with wines donated by all the area’s vignerons. The people who stayed here as patients were very poor and had probably never slept on a bed in their lives like those they did in their final days. They paid for none of their accommodations, or their food, or any of the care they received from the nuns who ran the hospital. The auction continues to this day and is one of the most prestigious wine events in the world. The money raised by the auction now goes to the new, modern hospital in Beaune, where everyone receives world-class French health care, and thankfully, most people survive their ailments.

The 13th century tile roofs at the Hotel Dieu (Hospices de Beaune)

The courtyard at the Hotel Dieu (Hospices de Beaune)

A tapestry of St. Anthony and the word medieval word Seulle (medieval for

seule, "the only one") which celebrates the strength of Nicolas Rolin and Guigone de Salins' love, who were the spouses who founded the Hospices de Beaune in 1443.

The next day we scheduled stops in the Côte de Nuits, north of Beaune and south of Dijon, where the most famous wines of Bourgogne are made. If you know anything about the area then you know the famous names—Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (DRC), Domaine Dujac, Leroy, Clos Vougeot, Richebourg, La Tache, Les Grands Echézeaux, Gevery-Chamertin, Chambolle-Musigny—all Grand Cru wines we could never afford let alone even try. Nonetheless, there were the vineyards right before us, easily accessible. This is part of the cult of Burgundy that I eschew. I have seen countless photos of people standing in front of the stone DRC marker, glass in hand, drinking some other maker’s bottle of wine, as if. (At the Michelin restaurant we ate at, a single bottle of the DRC was listed in their wine book for €12, 500) AS IF! It’s a bit like having your picture taken in front of the Ferrari dealership while you stand next to your Hyundai.

Fortunately, there are much more reasonable (I didn’t say affordable) wines and makers to see in the Côte de Nuits and luckily we were headed that way. We actually skipped the 10:00am scheduled tasting as we were starting to burn a little by this time in the trip, and wine that early in the morning wasn’t sounding all that great. I mean, jeez, it had only been a few hours since we finished the last bottle from the night before. But we did make it to our noon lunch reservation in Gevrey-Chambertin at Pierre Bourée's Table. This was a small country restaurant featuring Maman-style food. You know, your imaginary French mother’s cooking. And here was the lady, herself, greeting us, seating us, taking our order, and then running into the kitchen and cooking all of our food, BY HERSELF. And we weren’t the only people in the restaurant. There were maybe eight tables, and although we were first in—again, I need to learn to be less punctual—they were all full within a half hour. So here is this Maman, hustling. And all of it with a smile, with boisterous and riotous laughter, giving everyone just a bit of grief and making us all feel like we were visiting somebody’s home. On the chalkboard menu this day were two plats du jours; an entrée, main, and dessert for a set price. For my main, I ordered cabillaud, a fresh white cod served on top of rice covered in a velouté sauce that came inside a wide glass canning jar with the glass lid slightly ajar. OH MY GOD. It was so tender and delicious. Possibly the greatest cod dish I’ve ever eaten and I made sure that I told her so. “Mon Dieu, Madame. C'est tellement bon, tellement délicieux!”

During lunch, a man came through the front door that everyone seemed to know as he stopped at several tables and shook hands with the guests. We quickly figured out that this must be her husband and the namesake of the restaurant. He came to our table and asked us how we were enjoying our lunch, and we oohed and awed much to his satisfaction. We were drinking a bottle of white from Pernand-Vergelesses, a Bourgogne region a short distance away, and he told us that he was the winemaker of that bottle. He asked us if we wanted to see his cellar after we finished lunch. We had another scheduled tasting in just 45 minutes, but when fate intervenes, you have to roll with it. So, I sent an email to the next stop alerting them to our impending lateness, then we paid for lunch, thanked Maman profusely, and headed across the street, expecting a quaint cellar similar to the one two days before.

Instead of a knocker or doorbell, there was a handle at the end of a long rope at the door. We pulled it like we were calling our butler but we didn’t hear anything. Soon after the door popped open and there he was along with his son, a man in his early 30s. We learned that he was not actually Pierre Bourée, but Jean-Christophe Vallet, the great, great nephew of Pierre Bourée, who started the Domaine in the mid-1800s. Jean-Christophe was the fifth generation of his family to run the Domaine, his son the sixth, and this son had an 18-month-old girl who will be the seventh generation if she chooses to. We were taken into a foyer covered in mosaic tiles with oak walls and stained glass looking back onto a garden. After a brief explanation of the family history, we headed back out the front door and down the street five or six doors until entered another building, and there we were greeted with the sounds of a working winery. The noise of clinking glass bottles pierced the air as we saw them being loaded into a machine and automatically moving down the line to the filler where they were being filled and corked. This wasn’t somebody’s quaint family winery, rather it was clearly a mid-sized operation and a beehive of activity. We then headed downstairs to a large cellar and there we saw a young woman, who was the winemaker, tending to some barrels. We walked through several rooms full of barrels until we reached another area where bottles were being run through an old labeling machine by another man. Jean-Christophe told us that he bottled 100,000 bottles a year, but he didn’t label them until he received orders, many coming from overseas, particularly Japan. We could see the aged bottles being washed off and then dried before continuing down the line to where the label and the vintage year was applied to the bottle. He took us over to a cabinet where all of the labels were stored and another box of drawers where the vintage year labels were kept. We stopped and took pictures and shot some video of the man labeling the wines. It was all so manual but also vintage mechanical.

The foyer at Pierre Bourée et Fils

Pierre Bourée et Fils wine labels from the various Bourgogne regions where they make wine

The labeling machine at Domain Pierre Bourée at Fils

Checking the labels on recently labeled wines at Pierre Bourée et Fils

We then went upstairs and crossed over the working floor to another old, steep set of stairs, which we were led down, ducking our heads under a tiny doorway into a different cellar where thousands upon thousands of dust-caked bottles were sleeping in numerous dark and moldy rooms. Cage upon cage of ancient bottles, the years marked by small chalkboards, back through time they went. Jean-Christophe told me that even as he sold a lot of his wines each year, he liked to “keep his wines.” The oldest were from 1911, that’s just before World War I, and well before the Nazis came and tried to take it all in the early 1940s. He told me that he and his son had recently opened a bottle of 1922 Gevrey-Chambertin and it was still fresh and vibrant.

Jean-Christophe Vallet in the cellar of Pierre Bourée et Fils

After this amazing experience, we resurfaced into the light and then walked back down the street to the original house where we began. Each of us ordered some wine to take home which meant that the bottles needed to be found down in the cellar, then washed, labeled, and boxed for us. While we waited, we were allowed to wander the gardens behind the house. As we explored the large area, we picked sweet ripe cherries from an old tree. We rubbed our hands on the many wild herb bushes—oregano, thyme, rosemary—that grew in old urns throughout the yard, and smelled their piney scents on our fingers. Finally, we just sat and absorbed what we had experienced for the past two hours. After a quiet and reflective wait, Jean-Christophe finally emerged with our wines, but we now understood what it took to prepare a bottle of wine for sale at Pierre Bourée et Fils. The offer to “see his cellar” at lunch had turned out to be the best tour of our trip, and it was completely impromptu. I think because we asked intelligent and interested questions, he just led us deeper and deeper into his operations. What a gift. I will never forget it, and I don’t think Mark and Marie will either. When they open these wines sometime in the far away future, they will have an amazing story to tell whomever they deem worthy of sharing it with. We never did make it to the afternoon tasting, but fortunately I was able to email them the next morning and smooth it over, and they seemed to understand.

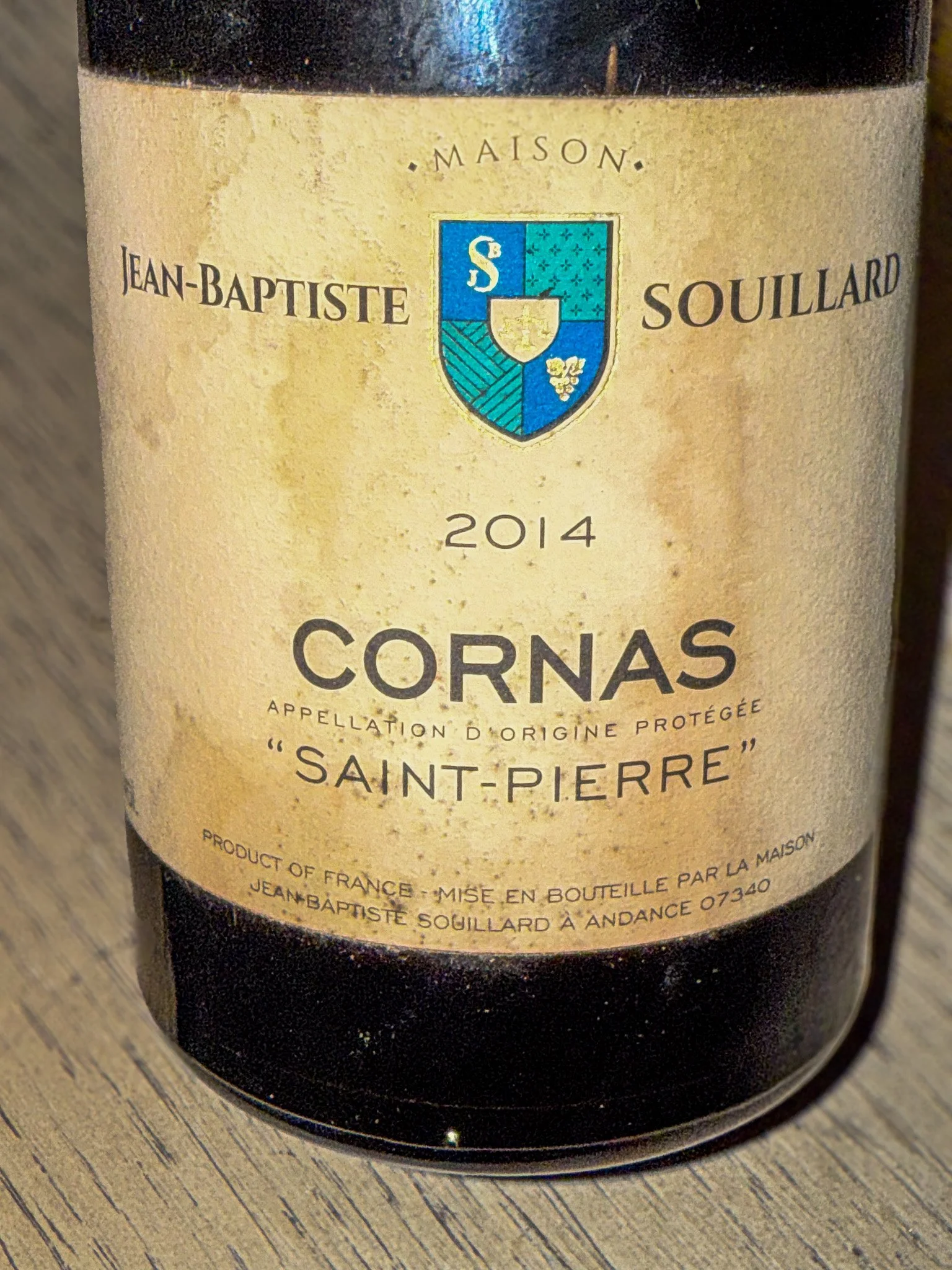

The wines we enjoyed during the week of our Bourgogne trip. We love our Rhônes, too.

Bourgogne has its hooks deep into me now. Admittedly, I have a very different perspective of “Burgundy people” now that I am one of the converted. I am probably one of those people now, too, but I do my best to just be enthusiastic about Burgundy.

I can’t help but think of one of my favorite movies, Sideways, and one of the saddest and most pathetic characters in cinematic history, Miles, played by the brilliant actor, Paul Giamatti. There is little that’s likable about his pretentious and annoying behavior through the early part of the movie, but as his character arcs, we begin to care about him. Midway through the movie he gives a vulnerable monologue about the grape, Pinot Noir, which was a perfect analogy for his tender personality, to the only person who seemingly understands him, Maya, played by the actor Virginia Madsen.

…“[Pinot Noir] It’s not a survivor like Cabernet Sauvignon, which can just grow anywhere and thrive, even when it's neglected. No, Pinot needs constant care and attention. You know? And in fact, it can only grow in these really specific, little, tucked-away corners of the world. And — and only the most patient and nurturing of growers can do it, really. Only somebody who really takes the time to understand Pinot's potential can then coax it into its fullest expression. Then, I mean, oh, its flavors, they're just the most haunting and brilliant and thrilling and subtle and ancient on the planet.”…

And she answers him with an even more thought-provoking and compelling reply, cementing his inevitable and immediate fall in love with her.

…“I like to think about what was going on the year the grapes were growing, how the sun was shining that summer or if it rained… what the weather was like. I think about all of those people who tended and picked the grapes, and if it’s an old wine, how many of them must be dead by now. I love how wine continues to evolve, how every time I open a bottle it’s going to taste different than if I opened it on any other day. Because a bottle of wine is alive—it’s constantly evolving and gaining complexity. That is, until it peaks—like your ‘61 [Chateau Cheval Blanc]—and it begins its steady, inevitable decline. And it tastes so fucking good.”

Regarding Bourgogne, nothing could be more true.